I didn’t study technology in school. I didn’t go to school for tech. I did English and women’s studies. I’ve had very little formal tech education. Almost all of my learning has been on the job […] Well, tinkering as a kid and starting to play on the internet when I was younger, but then I could figure out some things online and I could set up computers well for people, and parlayed that into working for nonprofit organizations in New York […] I applied for a few different non-profit-type jobs. I wasn’t sure what I was going to do. I might’ve still gone to grad school, who knew, but I applied for non-profit stuff at the time and then I also saw this one job at the (anonymous grant making Org), which was a job to basically create an online directory of community organizations in New York City. They needed someone who could be, essentially, the liaison between the organizers, like the actual organizations that they were going to be part of the directory, and the techies who they had found to build the database itself. They needed someone with some tech experience and knowledge but not tons, and then they needed someone with some organizer and activist experience, but not tons. I kind of fit the bill. That’s really how it launched, because that both gave me access to learning more about community technology and non-profit technology specifically. — MATIJA, WORKER/OWNER AT TECH COOPERATIVE

Our third research goal is to develop and share knowledge of practitioner experiences by establishing a baseline understanding of how individuals came to this work (career path), barriers and opportunities practitioners (and their communities) face, and the support practitioners may need now.

A summary of our key Practitioner Experiences findings is available in the Executive Summary.

PATHWAYS/EDUCATION/CAREER

Self-taught techies play important roles across the ecosystem

Many techies are self-taught, both in traditional tech sector work and in public, nonprofit, and tech coop work. Self-taught techies often have formal education in fields other than computer science. Practitioners had varied responses to the question of how they got their tech skills. Many said they taught themselves skills like web development, programming, system administration, or data visualization. Some took community college courses, others bought books and dove in, others went to coding boot camps, while many learned on the job and by watching others.

Self-taught techies’ career paths are sometimes circuitous. Some practitioners spoke about how they stumbled into the field of nonprofit technology. “[…] When I think back to it,” says Hibiki, a freelance digital security trainer, “I don’t really know how I would’ve ended up knowing the people that I know or being part of this community if I hadn’t randomly stumbled into it.”

Another practitioner who founded an international data-tech nonprofit said they got into this work because of a purely coincidental experience. “At the human rights organization, the administration and the organization decided that there was a bug somewhere in the office. Nobody really knew what to do with that information. They didn’t really know who to ask to find out where the bug was, or figure out how to even determine if there was one. I think because I was the only gringo in the office, for some reason, they were like, ‘You have to know people, go figure it out.’ So I ended up sort of feverishly emailing several people and being like, ‘I don’t know anything about digital security, I don’t know anything about bugs, who do I talk to, where do I go?’ And found myself trying to navigate all the different international networks […] to find that kind of expertise, and it’s really, really difficult. I ended up looking like an idiot walking around the office with headphones changing radio frequencies trying to find this very distinct radio signal that is transmitted by these bugs. We found the bug, it was great, it was a really empowering moment. […] So this got me really excited about the prospect of doing this kind of work, and that was where the (international data tech nonprofit) was born” (Becca, Executive Director of an International Data Tech Nonprofit).

The overall takeaway is that there is no defined pathway into this field. On the one hand, this means that there is certain kind of openness in the field to people who are led by their values. On the other hand, a lack of clear pathways may lead to better outcomes for people who already have strong personal networks, and these are shaped by existing social inequality.

You make it in this field with luck and conferences!

For self-taught techies to enter the field, they need luck, mixed with the ability to attend conferences and other networking events. Many practitioners said conferences and networking events were crucial spaces to find community. As one Non-Profit Tech Consultant who works in the U.S. and Canada describes: “[…] when I went to Allied Media Conference I had met people who were talking about nonprofit technology and I was like ‘What the hell is nonprofit technology?’ […] [Next] year I ended up going to Aspiration Tech’s Non-Profit Dev Summit in Oakland, and then I ended up getting opened up [to the] intersections of technology, policies, [and] social justice. So that was my gateway, to be honest.”

Beyond providing networking opportunities, self-taught techies and other practitioners identified conferences as critical gateways into this field. They said they used the Allied Media Conference, the Internet Freedom Festival, RightsCon, and Aspiration Tech’s Non-Profit Dev Summit to connect their interests in technology with their social justice work.

Not everyone is a self-taught techie!

Unlike self-taught techies, other practitioners have undertaken many years of undergraduate and graduate studies in computer science related fields to develop a career in this sector. Even though these folks have invested time in school perfecting their tech skills, conducting research, or teaching, mentorship and interest in public service is usually what propelled their career in this field. For instance, Artemis, a Phd. in Computer Science and a researcher at a nonprofit, left his grad school career in astrophysics and joined the School of Information at Berkeley. He explains, “I saw my future Ph.D. advisor give a talk that just blew my mind, where I realized, ‘Oh, people do that stuff, and they get paid to do that stuff, and I can do that stuff.’”

Even though they studied computer science, practitioners were not interested in taking up traditional computer science careers. Practitioners like Nyx, for instance, studied computer science and political science. They did not pursue a career in the traditional corporate tech sector, because they were interested in using their tech skills for public service. Nyx, who researches the gendered digital divide in the developing world, attributes his inclination to public service to mentors who encouraged him to think critically about technology and pursue interdisciplinary research. Many participants, like Nyx, joined this field because of mentors.

Others move beyond traditional computer science careers because they are “motivate[d by] the idea of being able to leverage new forces of technology for accountability, democracy, economic opportunity, and justice” in their everyday work (Baldev, Campaign Manager at Anon Foundation).

A small but growing number of formal educational programs are available to train people for this kind of work

There are growing numbers of university departments, centers, labs, and specialized degrees dedicated to the confluence of technology and society. Our research team assembled this spreadsheet (http://bit.ly/t4sj-programs) of educational programs related to the field. However, few of our interviewees or focus group participants reported being involved in them, probably because most are fairly recent programs.

More commonly, interviewees described majoring in fields in the humanities and social sciences, and teaching themselves, or learning informally, how to use technology to address those concerns. This is not to say that formal educational programs are not, and cannot be, key pathways into the work. Some participants mentioned that when they were in school, these programs either did not exist, or they were not aware of them. Others mentioned that even though they were interested in technology, another major fit their interests better than computer science. Therefore, universities need to develop more programs that teach a mix of tech skills across multiple roles, along with critical thinking and participatory design. These programs can train graduates for careers in public, private, or nonprofit technology work, and can mix the skills that are needed for successful tech project research development and implementation (not just programming).

Other successful programs and approaches to joining the field include some tech bootcamps and tech meetups

Some participants mentioned coding and technology intensive programs (commonly known as “bootcamps”), including a handful that are focused specifically on social impact, as important entry points. Some also mentioned tech meetups. Others, however, noted that the vast majority of bootcamps pay no attention to values, do not teach participatory or community-led design approaches, and tend to uncritically replicate the sexist, racist, elitist, solutionist, uncritical culture of mainstream tech firms.

Hacklabs, hackerspaces, and makerspaces are important

Some participants mentioned the key role played by technology-focused spaces like hackerspaces, makerspaces, and clubs, especially those that focus on supporting people from marginalized communities. A crowdsourced list and map of hackerspaces around the world is available here: https://wiki.hackerspaces.org/List_of_Hacker_Spaces.

Many different roles are necessary for the successful integration of technology in social justice organizations

We found that when it comes to tech for social justice, expertise comes in many forms—and in order to design technology that responds to community needs, many skillsets are required. Instead of putting those with software coding skills on a pedestal, diverse expertise needs to be recognized and valued. This includes people who can code, but also those who know graphic design, project management, user research, or design research, as well as those who teach digital skills, provide emotional support in times of digital threats, or manage and organize communications. Not everybody needs to learn how to code or to have particularly technical skills in order to be a valuable member of the technology for social justice ecosystem. Publicly recognizing and elevating those with diverse skill sets would also lay the groundwork for more people to join the ecosystem, particularly if they don’t have coding skills.12

SUPPORT & OPPORTUNITY (PERSONAL/ORGANIZATIONAL)

Individuals from underrepresented backgrounds need greater access to opportunities, relationships, and support resources.

Fellowships, internships, and mentorship provide key opportunities

When asked to describe the kinds of support that propelled their careers, many practitioners mentioned internships and fellowships as key opportunities. As one practitioner put it: “my internship at the EFF […] was an extremely valuable experience, and probably my first real professional experience working on tech policy issues.” Internships and fellowships give folks opportunities to learn, explore, and network. For some, they provide a pathway to employment. These opportunities are important for all practitioners. However, to expand opportunities for individuals from working class backgrounds, internships and fellowships need to provide a living wage.

Similar to internships and fellowships, quality mentors can provide essential support to practitioners. Many said that mentors changed their career trajectory. Gertruda, a digital researcher, says: “I had a very excellent boss who allowed me to trade [my] technical skills for learning other skills like writing grant proposals, writing budgets, how to manage people, and these sorts of things. Having that mentorship in the right position and being able to trade skill sets for learning other skill sets really gave me the tools and contacts that I could use to survive [in this field].”

Practitioners said they sought mentors when they first moved into this field, or when exploring new skills and areas of expertise. “After I graduated from design school,” said one, “[…] I knew that I wanted to have my own studio, but I also didn’t feel as though my design education had fully prepared me, in terms of the craft of the work. And so I wanted to study more under somebody who I really respected, as far as design went.” Therefore, internships, fellowships, and mentorships are essential to bring new talent into this field. These opportunities give those that do not have the work experience, the privilege, or the “right” background a chance to break into this field.

Conference scholarships for underrepresented individuals

Conferences are essential gateways into this field. In particular, practitioners identified the Allied Media Conference, Internet Freedom Festival, Aspiration Tech’s Non-Profit Dev Summit, and RightsCon as pivotal spaces to develop their careers. A digital security trainer with an underrepresented background puts their experience this way: “I went to this conference in Valencia called the Internet Freedom Festival, it was a surprisingly pivotal moment […] I showed up here and there are all these amazing people. [After coming back from IFF], I started doing digital security training at libraries.”

When practitioners make their way to Detroit or Valencia, they find like-minded people who challenge the pervasive perception of technology as apolitical. One practitioner says these conferences are also spaces where they find camaraderie and realize that they are not alone in this work. “It is not just the style of the event,” they say, “it’s also who shows up. The bunch of people that, they’re the only person like them in their organization, or they founded an organization, or they’re just trying to figure out how to help out, and you get to see that you are not alone.”

However, attending these conferences is not easy. Low income individuals often do not have resources to cover travel, accommodation, and other conference-related expenses. And when conferences provide diversity scholarships, they usually have long applications processes that require applicants to write essays and attend interviews. Many practitioners put in many hours of work applying for scholarships that often support only a few people with underrepresented background. Therefore, fully funded conference scholarships with simplified application processes that target underrepresented individuals are key to growing a more inclusive field.

BARRIERS (PERSONAL/ORGANIZATIONAL)

We asked practitioners to describe the barriers and challenges that they faced in entering this field.

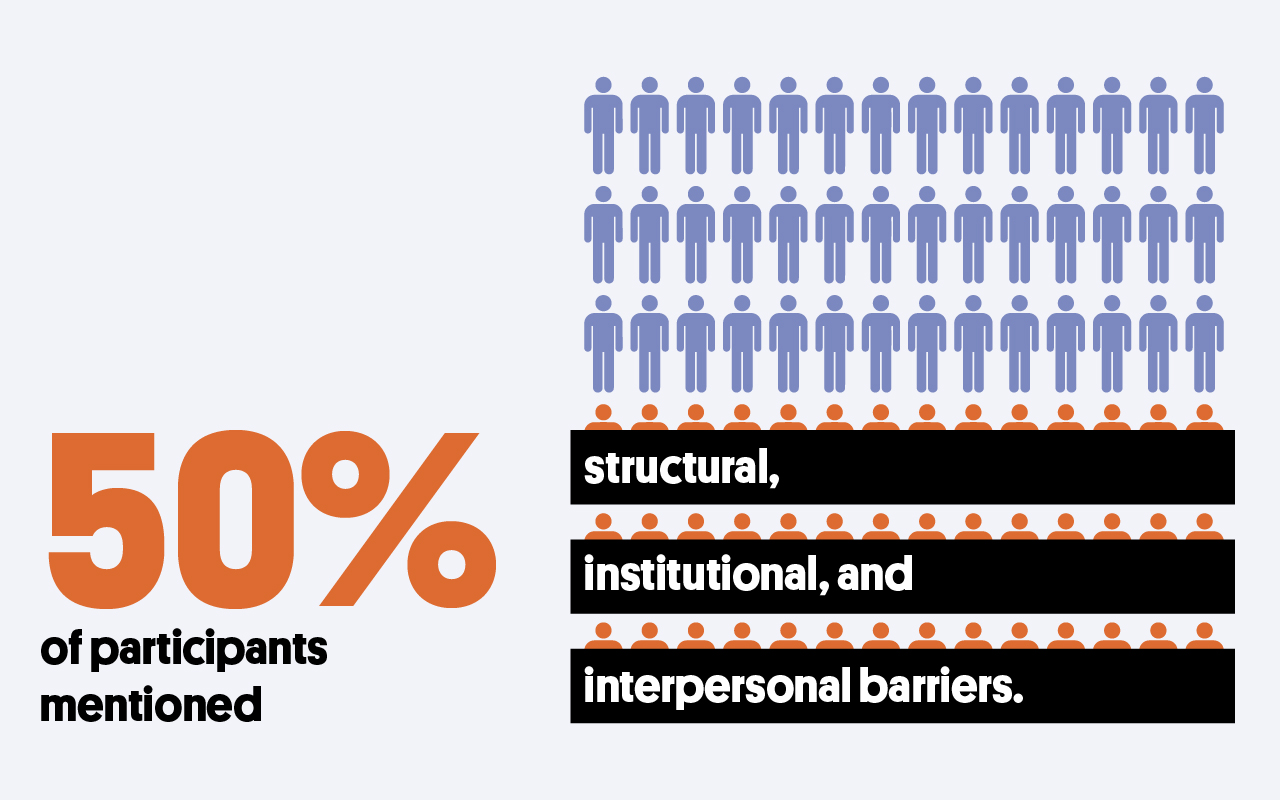

50% of participants mentioned structural, institutional, and interpersonal barriers

Participants described racism (33%), sexism (33%), transphobia (10%), ageism against older practitioners in the tech industry and against younger people in civil service (9%), classism (9%), and homophobia (8%). Discrimination based on race, class, gender identity, sexual orientation, disability, and their intersections lead to practitioners feeling unsafe, and make it difficult for some to continue working within this ecosystem. Other barriers mentioned by practitioners include difficulty finding community (29%), a lack of tech integration with core organizational work (22%), difficulty accessing educational programs (14%), and high participation costs.

Cost of participation

The prohibitive cost of attendance excludes significant swaths of newcomers, independent contractors, young people, and People of Color, who often have less access to independent or institutional financial support. While scholarships can be helpful, applications can be long, often only cover part of the cost of registration, and rarely cover the cost of travel and accommodation (Friedemann, Advisor of Tech Projects at a Government Office).

Ageism against older practitioners in the tech industry and younger practitioners in civil service

A few participants mentioned that in the broader technology industry, there is a form of ageism against older employees, who are often stereotyped as out-of-touch and inexperienced with technology (Blair, fellow for a legislative body). Meanwhile, in government positions, ageism can often go the other way, as there are few jobs for junior staff, and seniority and age hold significant weight (Friedemann, advisor of tech projects at Government Office).

Sexism

Many women practitioners said they had to learn to navigate being a woman in this field, often in brutal ways. Women’s experiences ranged from being catcalled on stage, to working in hostile environments where their technical expertise was continuously questioned or ignored, to having to deal with condescension from their male colleagues, to being solely and thanklessly responsible for keeping known sexual predators out of work environments (Vishnu, Founder of a Nonprofit). When women do not possess coding skills—and sometimes even if they do!—the other knowledge they hold is deemed irrelevant.

Racism remains pervasive

Hiring, advancement, retention, salaries, funding practices, and educational opportunities, among others, are all areas where People of Color face discrimination in this field. People of color only get access to a fraction of the positions, promotions, and grant opportunities. One participant pointed out that People of Color are not “allowed” to be mediocre in this field, and being exceptional also does not guarantee access, recognition, and equal pay. Most organizations do not gather or share demographic data about their employees, volunteers, leadership, boards, or grantees, further obscuring pervasive racism. Few organizations in the field have specific plans to address diversity and inclusion, and when they do have strategies, they fail to publicly disclose their plans.