I think there’s a lot of small grassroots and community-based organizations that are doing really, really great work and hustling really, really hard, and because they’re so small and because they work specifically with People of Color, they definitely do not get the recognition that they deserve, and they don’t have access to opportunities like other bigger NGOs. — HIBIKI, DIGITAL SECURITY TRAINER

We try and, through the course of relationships with organizations, not just help them do a technology project but at the end feel way more confident, way more powerful when they’re talking to technologists, when they’re talking to data people. They’re bringing the political understanding, the contextual understanding, the fantastic ideas, they have something to contribute to those conversations when often times, historically, they felt like an idiot in those conversations. Trying to give people the language, the understanding, the feelings and confidence, that come along with having one successful project under your belt. — BECCA, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR AT AN INTERNATIONAL DATA TECH NONPROFIT

Our first research goal is to define the field(s) and inventory the current ecosystem. A summary of our key Ecosystem findings is available in the Executive Summary.

DEFINITIONS & FRAMING

Practitioners use many different terms and frames to talk about this ecosystem.

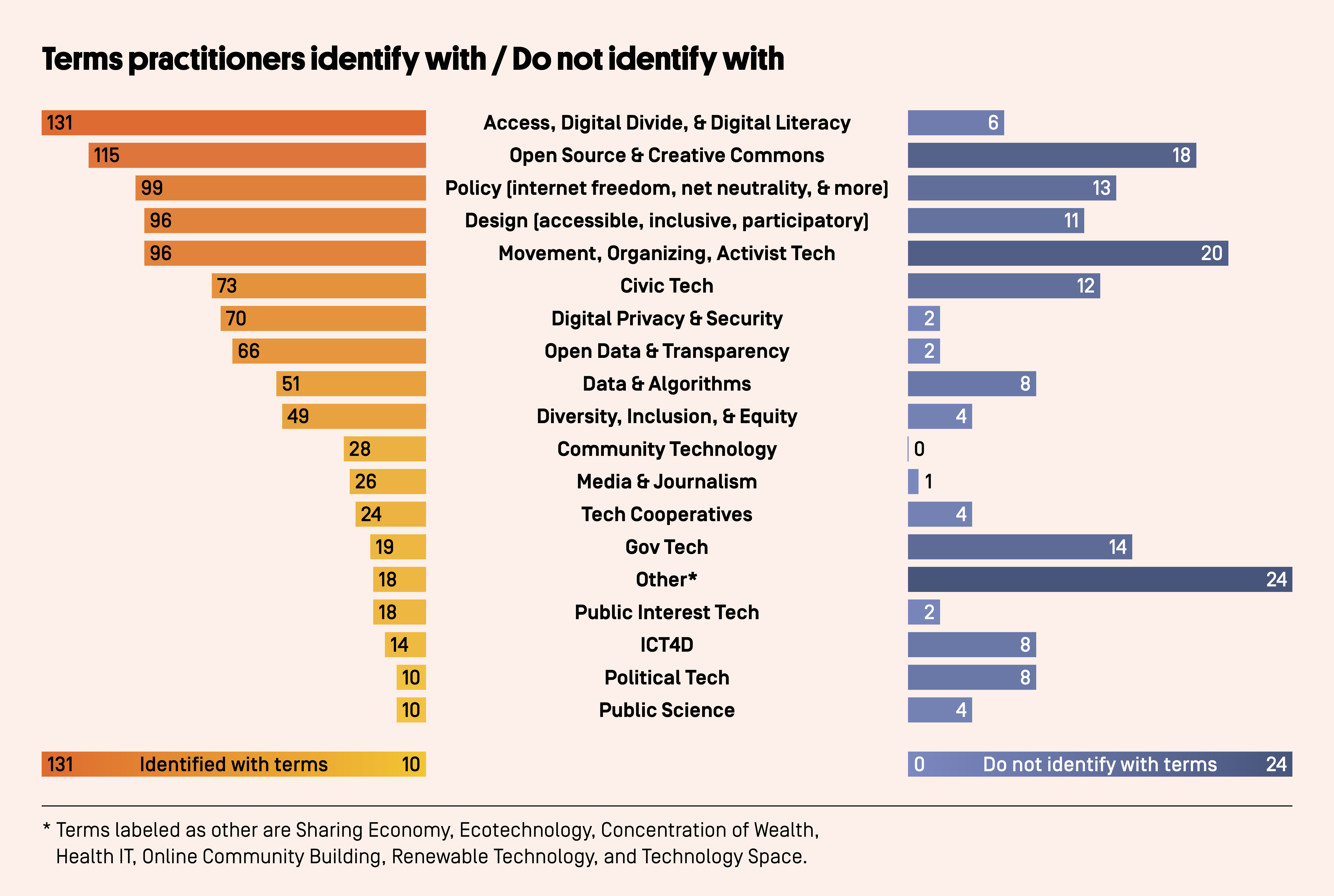

We found that people use many different terms and frames to talk about the work they do. In our interview and focus group process, we provided participants with a list of terms used in the various overlapping fields, and asked them to circle terms they identified with, cross out terms they felt did not belong, and suggest missing terms that they use to frame their own work. We then facilitated discussions about why practitioners choose to identify with some terms, and why they do not identify with others. Ninety-six study participants completed this terms worksheet, and provided us with 252 different terms that they use to describe their work. We then coded all 252 terms into the following top-level categories:

Table: Terms & Top-Level Categories

| Category | Terms |

|---|---|

| Access, Digital Divide, & Digital Literacy | access to tech, access to technology, accessible tech, accessible technology, data literacy, digital divide, digital equity, digital justice, digital literacy, digital redlining, tech access, technology access, technology accessibility, universal access, universal design |

| Civic Tech | civic crowdsourcing, civic innovation, civic tech, civic tech for good, civic technology, civic technology for good, tech for social good, technology for social good |

| Community Technology | community tech, community technology |

| Crisis & Disaster Response | digital crisis response, digital emergency response, digital humanitarian, digital response |

| Data & Algorithmic Bias | algorithmic accountability, data for good, data justice, data science, data science for good, data vis, data visualization, data-driven justice, public data, algorithmic transparency, responsible data |

| Design (accessible, inclusive, participatory) | accessible design, centering the needs of communities who aren’t traditionally creators of technology, citizen design, citizen experience design, civic design, civic HCI, civic map, civic UX, codesign, collaborative design, community centered design, community design, community driven design, community led design, community map, community-centered design, community-led design, critical design, design for good, design justice, design thinking, HCD, HCI for good, human centered design, human computer interaction for good, inclusive design, participatory design, public design, public HCI, public interest design, public map, public UX, social impact design, social justice design, technology that meets human and global needs, User centered design, UX for good, UX for social good |

| Digital Privacy & Security | anti-surveillance, consentful tech, consentful technology, counter-surveillance, digital security, encryption, HIPAA, holistic security, privacy, privacy tech, privacy technology, surveillance |

| Diversity, Inclusion, & Equity | abolition, black girls code, black tech, culture setting, data discrimination, diversity in creators of tech, diversity in tech, fair housing, fair lending, feminist technology, gender and queer, girls code, harassment/discrimination in the tech/social justice sector, inclusivity and safespace, latina tech, latino tech, latinx tech, lesbians who tech, racial justice, social justice, tech diversity, tech in plain language, technology diversity, trans tech, trans* tech, women in tech |

| Govtech | connected cities, connected city, e-government, government in-sourcing, government technology, government tech, smart cities, smart city |

| ICT4D | appropriate tech, appropriate technology, ICT4D, information and communication technology for development, information and communication tech for development |

| Media & Journalism | data driven storytelling, data journalism, data-driven story, data-driven storytelling, digital media and public responsibility, independent media |

| Movement, Organizing, & Activist Tech | digital autonomy, digital organizing, digitech organising, grassroots map, hacktivism, hacktivist, liberation tech, media justice, movement tech, movement technology, research justice, revolution tech, revolutionary tech, tech activism, tech and revolution intersection, tech for revolution, technology activism, technology and revolution intersection, technology for revolution, using technology for social justice |

| Nonprofit Tech | non-profit tech, non-profit technology, nonprofit tech, nonprofit technology, non profit tech, non profit technology, tech, technology |

| Open Data & Transparency | government transparency, open data, open gov, open government, open research, ownership, public data, sousveillance, transparency, work open, work open lead open |

| Open Source & Creative Commons | creative commons, F/LOSS, FOSS, free and open source software, free hardware, free software, free/libre and open source software, free/open knowledge, open internet, open net, open source, open source hardware, open source software, open web |

| Other | concentration of wealth, criminal justice, ecotech, ecotechnology, health IT, human rights, online community building, renewable technology, renewable technology, sharing economy, tech space, technology space |

| Policy (internet freedom, net neutrality, & more) | digital sovereignty, evidence-based policy, HITECH Act, internet freedom, net freedom, net neutrality, public broadband infrastructure, public tech infrastructure, public technology infrastructure, public wireless spectrum, tech policy, technology policy |

| Political Tech | political tech, political technology |

| Public Interest Tech | public interest tech, public interest technology |

| Public Science | citizen science, public science |

| Tech Cooperatives | cooperative business models, platform coop, tech coop, tech cooperative, technology coop, technology cooperative |

We tallied the individual terms that practitioners circled, and also summarized these findings by top-level categories in the table below. The most frequently circled terms related to the categories of Access, Digital Divide, and Digital Literacy (circled 131 times), followed by Open Source & Creative Commons-related terms (115); for example, nearly half of practitioners identified with “free software” (40 of 96 practitioners circled this term). Policy-related terms (such as “tech policy,” “net neutrality,” or “open internet”) were circled a combined 99 times. Design-related terms (circled 96 times), focused on accessible, inclusive, and participatory design, among other similar terms, were nearly as popular as Policy terms, as were terms focused on Social Movement, Activist, and Community Organizing tech (96). Popular individual terms included “open data” (37); “privacy” or “security” tech (36 and 31); “digital literacy” (35); the “open web” or “open internet” (30); “community technology” (28) and “civic tech” (28), and “tech policy” and “inclusive design” (each 27). About one in five participants (18 out of 96) identified with the term “public interest technology.” The individual terms that people found most problematic were “smart cities” and “sharing economy.”

Differences between terminology and framing are important and should not be erased.

What is more, many participants felt that differences between terminology and framing are important and should not be erased. Different terms and frames resonate for different actors in this space. It’s best to understand the range of terms and frames that people use to do excellent work leveraging technology to advance the public interest, the common good, social justice, government and corporate accountability, and so on.

For example, some see “civic tech” as a field of practice that is predominantly white, male, U.S.-centric, and institutionalist. Stevie, a Tech Fellow at a Foundation, struggled with terms like “technology for social good” and “civic tech.” For him, these terms put the technology first, rather than the people, and he believes that “anyone who’s doing good work would be more specific than that.” He finds it hard to identify with “civic tech” because he feels civic tech spaces are very U.S.-centric, very white, very technocratic, and their work is usually not about social justice.

Kimberley, a Founder of a Digital Rights Org, uses an inclusive definition of technology. She and her organization see technology as part of their liberation strategy, but do not consider technology to be their sole tool. They weave many old and new strategies together, and due to that, other “tech” organizations have a hard time understanding orgs like them that are led by women, PoC, and gender nonconforming folks.

Arata, a Technology Capacity Builder, feels that the term “public interest” connotes policy, power, and privilege, and does not connote work with frontline communities. Additionally, they emphasize that most of the technology work being done in nonprofits right now can be described as stopgap, and is being done by “accidental techies.”

Some women and PoC participants do consider themselves technologists. Other people we interviewed do not identify with the term “technologist,” even if they work extensively with technology. A few, mostly women, have specifically been told by men that they are not technologists, even if their work focuses on technology.

For example, Alda, a Community Organizer and Consultant at a National Newspaper, does not consider herself a technologist. She said that this is because she has been around men who are programmers who have made it clear to her that she is not a technologist, even though her whole job involves technology.

Richard, a Broadband Expansion Manager for a Rural City, feels that the term “technologist” is a coastal term. He said that other than coastal folks, everyone else in this field sees themselves as engineers. He suggested we do a spatial analysis to see if there is a correlation between the terms people identify with and their location in the country.

Some participants related that they use the language of social justice and/or community technology, and often find civic tech spaces alienating. One noted that just as there is both “public interest law” and “movement lawyering,” we need both “public interest tech” and “movement tech.” These may overlap, but are not the same thing.

While the literature provided definitions of many of the most widely used terms, this section focuses more on interviewee perceptions of the most contentious terms. This approach prioritizes practitioner knowledge and avoids top-down naming and framing.

Practitioner perceptions of “Civic Tech”

- Civic tech as distinct from “gov tech:” While most participants drew a connection between civic tech and government, a few more intimately familiar with the spaces of civic and government technology made the distinction that “gov tech” is technology created within the government, or to be used directly by governments, and “civic tech” is that created outside of the government, often by volunteers.

- Civic tech as an umbrella term: Some participants used civic tech to broadly refer to any use of technology for social good, including technology for social justice, technology for governance, technology for liberation, and technology for the public interest. Others, however, gave it a more specific definition, or felt that while the ideal may be for the term to encompass every attempt to use technology for social good, civic tech practices do not usually live up to that ideal, because they often exclude the communities they intend to benefit from problem framing, design, testing, and implementation.

- Civic tech as a privileged framework: A number of participants noted that civic tech tends to refer to a field of practice that is predominantly white, male, U.S.-centric, and “mainstream” or “establishment.”

Practitioner perceptions of “Community Technology”

- Community technology as determined by community needs, and designed by community: Several participants defined community technology as a way of working with technology that starts with needs sourced from a particular community, and collaboratively designed with that community.

- Community technology as a way to improve access to technology and information: Additionally, many participants highlighted a focus of community technology projects on access to the internet, level of comfort with and ability to use technology, and information for people who have been traditionally excluded from, or attacked with, digital technology.

Practitioner perceptions of “_____ For Good”

- “For good” is vague but ok: A few participants (about 20) used or accepted the idea of technology “for good” as a vague but positive umbrella term. However, a similar number of participants were skeptical of the simplistic promises of the phrase.

- “For good” as too broad to be useful: Some considered it simply too broad to be meaningful, and felt that it doesn’t clearly define a type of work or focus area.

- “For good” as actively manipulative: A few were skeptical of the term because they consider it to be actively manipulative of people’s goodwill, without substance. One noted that because the more specific part of the term comes before “for good” (for example, “data science for good,” “tech for good,” or “UX for good”), these framings put technology and technologists first, and typically do not involve community-based leadership.

Practitioner perceptions of “Public Interest Technology”

- Public interest technology as government, policy, and law: While most participants had not heard of the term “public interest technology” or “public interest technologist,” and the ones who had considered it a broad umbrella term, some gave examples of public interest technology in government, tech policy, and public interest law. A few participants who did not identify with the term noted this specific focus of the work.

- Public interest technology as technology for something other than profit: Some participants defined “public interest” or “public interest technology” as any work that falls outside the profit motive or the market. Some referred to it as technology work that happens within NGOs or non-profit organizations.

- Public interest technology as advocacy: Many participants defined “public interest technology” as the advocacy work done to keep the internet open, innovative, and free, often by policy-focused non-profits.

- Public interest technology as a top-down, non-diverse framework: Some participants who did not identify with the “public interest technology” framing, and some who did, identified a lack of diversity as a significant issue in the nascent community. It was considered to be predominantly white, male, D.C.-focused, and funder-driven.

Practitioners do not always identify as “technologists.”

We also asked practitioners to describe their own work and roles, talk about who they collaborate with, and share who they see as field builders. We spoke to people who identified as community organizers, lawyers, software engineers, project managers, researchers, volunteers, leaders of volunteer organizations, data scientists, digital security trainers, a city manager, and many other roles. When asked to identify their role(s) in the field, half (52%) of participants selected “technologist,” while 40% selected “community organizer” (participants were able to check as many roles as they identified with). For more detail, see the Participant Demographics section.

As one practitioner described, “I don’t actually think of myself as somebody in particular who works in technology or the tech sector, or refer to myself as a technologist” (Alun, Technology Advisor for a City Government on the East Coast). They described how they chose not to pursue coding, but instead to contribute their knowledge and skills to the design and democratic governance of technology. Many practitioners shared that they identify with multiple roles; these sometimes include “technologist,” but other identities are also important. A Tech Fellow at a National Think Tank shared that the roles they identify with have shifted over time: “So if you were to say, are you a technologist, even three months ago, I would say no. Because I am not a coder or a programmer or even a designer, because I am an educator, I am a practitioner. But when we started to kind of define or think about the narrative of public interest technology, we get to really define what technologists are. And so thinking within the greater context of all of this work that we’re doing, we kind of zoom back and said, we’re researchers, we’re designers, we do have some of the coding and programming. But we’re also change agents” (Zdravka, Tech Fellow at National Think Tank).

Partnerships, informal networks, and volunteerism

Practitioners described a wide range of partners that they collaborate with, including volunteers, state, local, and federal government agencies, humanitarian and disaster response organizations and agencies, businesses, funders, civic tech organizations, community-based organizations (CBOs), social movements, open source software contributors, legal aid organizations, and university students.

Social justice organizations and movement practitioners are particularly explicit about partnerships. For instance, Tivoli, a Freelancer and UX Research at a Tech Corporation, makes very conscious decisions when it comes to who she works with. While part of an open science project funded by a venture capitalist, she was forced by the funders to do certain things that did not match with the vision of the project, and as a result, left her job. She worked with people who identified as civic technologists, and felt that they often did not want to make anyone uncomfortable, and were apolitical. Due to these experiences, she no longer works with venture capitalists or civic technologists.

Some social justice organizations refrain from working with large internet firms. For instance, Arata’s nonprofit was approached by Facebook to collaborate, but Arata and her team refused because of Facebook’s nature as a profit-seeking multinational corporation.

Others leverage multistakeholder process with diverse actors from the public and private sectors, academia, and civil society to work around common interests. Katerina, Co-Founder of a Media and Community Organizing Nonprofit, works in collaborations across large national and small grassroots organizations to further enhance their movement and advance towards their goals. For instance, a large national investigative news organization picks local news organizations to collaborate with, rather than other national media houses. They do that when the stories they cover affect a specific community, and they would rather partner with a local media house that is based in or close to that community. Practitioners who reside in rural areas, or are the only technologist in a nonprofit, often use networking events and convenings to find collaborators.

Volunteerism has its limits. Dan, a CEO and Founder of a Civic Tech Organization, felt that the civic tech field has pushed volunteerism to its limit, and as a result, volunteers are getting burnt out. Additionally, he feels that civic tech has hit a ceiling in funding, and that many organizations find it difficult to sustain themselves.

Who controls dominant framings?

“If people are really gonna be there for us, personally, I feel like they should be there for us in the way that we would like to present ourselves, you know? And not always try to direct, or control what we do so much.” — Godtfred, Technology Fellow at a Youth Nonprofit

Practitioners, and particularly nonprofit practitioners who are responsible for fundraising for their projects, consistently describe private foundations as frame-setters. While frames for work across this ecosystem vary and may come from organizers, community members, educators, and/or researchers, most practitioners described feeling pressure to frame their work in a particular way in order to have access to funding streams.

For example, Godtfred, a Tech Fellow at a Youth Nonprofit, noted that in this field, like any field, you have to play the political game to get funding. They felt that the way we frame our work opens and closes doors, and determines funding opportunities. They said that you have to “jump through hoops” to get funding, but felt that “if funders are going to be there for us, they should be there for us without controlling our framing and our analysis.”

Other participants described the need to change their language in different contexts, use certain frames with funders, and re-frame for allies or constituents. Katerina, a Co-Founder of a Media and Community Organizing Nonprofit, argued that “code switching,” or the ability to translate speech styles, terms, and concepts between different contexts with different audiences, is a core competency, and that an over reliance on specialized terminology can be ultimately classist.

In addition to funders, other powerful players that influence how people frame their work include politicians, who set policy agendas, and people who write job, fellowship, and internship postings. One practitioner working in City Government noted that, since efficiency is not the core value of government, they needed to develop a very different narrative about how and why technology can have a positive impact. For them, advancing projects requires the ability to tell a story that aligns with the values of people working inside government agencies. At the same time, they feel that government digital services are judged by the public according to the usability standards of Amazon, Google, and Facebook products (Rob, CTO of a City Government).

UNDERSTANDING THE CURRENT ECOSYSTEM

We used various approaches to gain a sense of the scale of the ecosystem.

In the first stage of research, we developed a database of information about more than 700 organizations and projects, available both as a spreadsheet (http://bit.ly/t4sj-orglist) and via a searchable web interface at https://morethancode.cc/orglist/. We initially seeded this with the organizational list from the Civic Tech Field Guide (available at http://bit.ly/organizecivictech), then added new organizations that came up in project interviews, focus groups, and workshops. The database is searchable by type of organization and sorted into the top-level categories that emerged from our research process, as well as by variables such as “Majority PoC” and/or “Queer.”

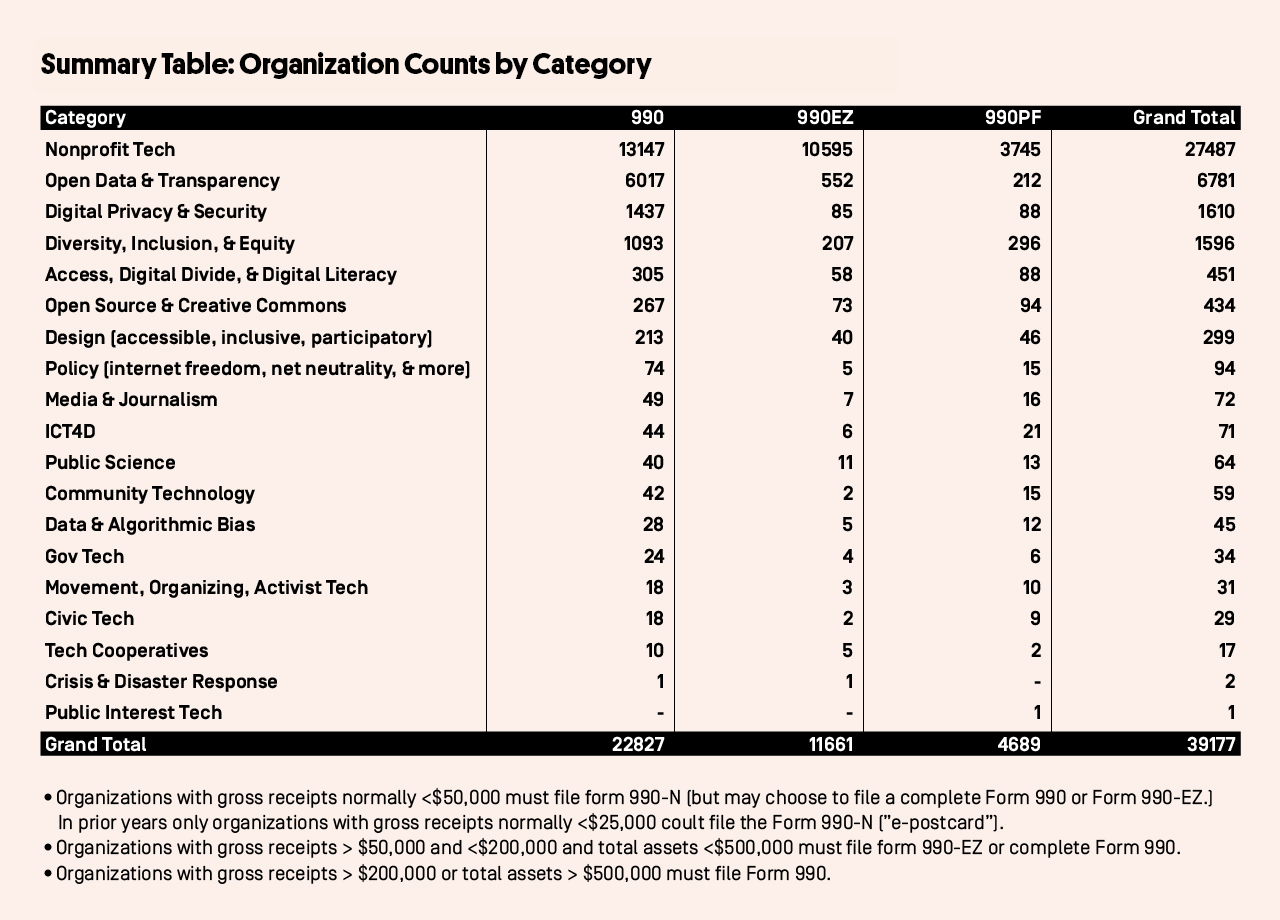

In the second stage of research, we decided to build a more comprehensive database of relevant organizations by using U.S. IRS Form 990 data provided by the Nonprofit Open Data Collective. We searched through over 450 million records in that database for relevant organizations, based on the 252 different terms that study participants use to describe their work (the terms list can be found here: http://bit.ly/t4sj-terms).

The search process described above returned 91,058 unique organizations (foundations and nonprofits) who use one or more of our practitioners’ terms somewhere in their 990 Forms, e.g. in mission statements, program descriptions, or grant descriptions. However, some of the terms provided by practitioners are quite broad and apply to many organizations that may or may not specifically engage in technology work (for example, “criminal justice”). We reclassified these broader terms as “Other.” When we exclude organizations that we classified as “Other,” we are left with 39,000 nonprofit organizations who included one or more of our practitioner-identified search terms in their tax forms.

From there we further analyzed the data by our top-level categories:

The majority of organizations in this ecosystem appear to work on nonprofit tech. After that, open data and transparency is the second most populated organizational space, followed by organizations working on digital privacy and security, or diversity, inclusion, and equity. We recognize that at this stage there are likely many false positives, and the data requires additional cleaning and analysis. We encourage others to further explore and analyze the data here.

Besides quantitative data about nonprofits in the ecosystem, we would like to highlight two specific kinds of organizations that participants mentioned as important: libraries and community colleges.

Libraries are important sites. Terry (Policy Director of a Public Library) argued that digital equity is one of the primary responsibilities of libraries, and that libraries are the key element of civic infrastructure addressing this challenge, although they may not always do so strategically. Similarly, Vishnu (Founder of a Nonprofit) felt that libraries are critical sites for reaching communities that have been ignored by the infosec and digital security worlds, but who paradoxically live with the highest levels of risk: People of Color, poor people, and formerly incarcerated people.

Community colleges are important. Ileana (CEO, Digital Advocacy Company) argued that community college, as a low-cost way to gain computer science skills, often with financial aid available from the government, provides a critical piece of the ecosystem.

Funding is unequally distributed among the various subfields in this space, in ways that replicate structural inequality.

Our analysis of form 990 data indicates that the key funders of the ecosystem are the Ford, Knight, Rockefeller, MacArthur, and Hewlett Foundations. Data about how frequently these funders used our ecosystem search terms in their 990 forms are explorable here. We are in the process of further analyzing 990 data to better understand the distribution of funding between organizations and categories, and we will provide that analysis as it becomes available.

Study participants shared that, in their experience, national nonprofits, organizations led by white cisgender men, and organizations in large coastal cities receive the lion’s share of funding. For example, Dishad, an Eco Justice Community Organizer, feels that smaller, grassroots, and more radical organizations are discriminated against by funders, in favor of large, national nonprofits that more closely align with the interests of their corporate boards. Candide, a Co-Founder of a Nonprofit Coding School, feels that, despite a track record of success, as a “non-traditional founder” (i.e. a woman of color) she struggles to get funding as easily as her white male peers in the startup space. Nessa, a Journalist and Founder of a Nonprofit, notes that noncoastal areas are “funding deserts,” where it can be difficult to sustain critical work. Additionally, her organization takes a deliberately local approach and focuses on the unique needs of youth in her county.

Dan, a CEO and Founder of a Civic Tech Organization, feels that civic tech has hit a ceiling in funding, and that many organizations find it difficult to sustain themselves.

Manuel, a Founder of a Civic Tech Organization and a For-Profit advocacy company, notes that philanthropy can have a distorting effect on communities, because it can undercut work that is already operating sustainably. He shared the example of a FOIA automation business that was undercut and killed off by a foundation-backed copycat. He also says that the technology field is overwhelmingly white and male dominated, and that organizations need to take proactive steps to prioritize the leadership of women and People of Color, and to use codes of conduct to keep spaces accountable.

Mel, an Executive Director of a Nonprofit, notes that funders often focus on “parachuting” technologists into organizations, or on isolated technology projects for social good, devoid of context, when the real need is capacity building.

Judyta, a Facilitator at an Education Technology Collective, shared that they see a lot of funding for university-based STEM projects that fit industry needs and profit motives, but not for projects that include critical questioning or feminist critical thinking. They also note the stark difference between the developers, creators, and users of technology, and highlight the undue focus on developers and the disregard for end users.

Erica, a Fundraiser at a Foundation, sees sustainability as a blind spot in this field. When core funding changes, key players evolve, merge, or spin down. She says that funders are not ready to ensure that the work continues to serve the people it was designed to serve. She also feels that we don’t think enough about how to ensure that our projects are freely and openly accessible for generations to come, because the space is so rapidly evolving, and it’s very hard to think beyond a two- to five-year cycle.

Successful funding strategies

Lulu, a Technology Project Funder at a National Legal Nonprofit Funder, funds technology initiatives within legal aid services across the country, so that attorneys can “work at the top of their license.” He wants to automate most of the day-to-day work of legal aid, so that when attorneys sit with their clients, they have all the information they need to help them. However, one of the biggest challenges he faces in doing this work is the lack of integration of user-centered design at the start of projects, and the inability of developers and coders to write code and develop products in plain language that users of all ranges can understand.

Artemis, a Technologist at an International Policy Technology Nonprofit, feels that it is very important to organize and fund “water cooler”-type convenings for the people who work across disparate parts of this space.

Friedemann, an Advisor of Tech projects at a Government Office, highlights that the funding strategy of providing unrestricted operating funds, rather than metrics-driven return on investment and tightly restricted funds, while no longer popular among funders, was critical to motivating people to explore, self-actualize, and create innovation.

More stories of successful strategies are available in the Stories of Success section.