Executive Summary

OVERVIEW

Our society is in the midst of an extremely urgent conversation about the benefits and harms of digital technology, across all spheres of life. Unfortunately, this conversation too often fails to include the voices of technology practitioners whose work is focused on social justice, the common good, and/or the public interest. Every day, technology practitioners in government agencies, nonprofit organizations, colleges and universities, libraries, technology cooperatives, volunteer networks, and social movement organizations work to develop, deploy, and maintain digital technology in ways that directly benefit their communities. These practitioners include software developers, designers, and project managers, as well as researchers, policy advocates, community organizers, city officials, and people in many other roles.

#MoreThanCode aims to make the voices of these diverse practitioners heard. Our goals are to I. explore the current ecosystem; II. expand understanding of practitioner demographics; III. develop and share knowledge of practitioner experiences; IV. capture practitioner visions and values; and V. document stories of success and failure. We focus primarily on practitioners who work in the United States.

This report was produced by the Tech for Social Justice Project https://morethancode.cc/, co-led by Research Action Design (RAD) and the Open Technology Institute at New America (OTI), together with research partners Upturn, Media Mobilizing Project, Coworker.org, Hack the Hood, May First/People Link, Palante Technology Cooperative, Vulpine Blue, and The Engine Room. NetGain, the Ford Foundation, Mozilla, Code For America, and OTI funded and advised the project.

Methods: #MoreThanCode is a Participatory Action Research (PAR) project. All research partner organizations worked together to develop the research questions, study design, data collection and analysis, conclusions, and recommendations. We interviewed 109 people and conducted 11 focus groups, with 79 focus group participants. A total of 188 individuals participated in the study. We sought diverse participants in terms of gender identity, sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, educational background, sector (government, nonprofit, tech coop), urban/rural location, and other factors. Our study focused primarily on practitioners in the United States. Detailed study participant demographics can be found in the main body of the report. We also collected and analyzed secondary data, including: a database of 732 organizations and projects; IRS form 990 data for over 40,000 relevant nonprofits; over 14,500 job listings; and over 350 educational programs, networks, and associations. The Appendices include detailed methodological information, links to relevant secondary datasets, and links to interactive tools to further explore study data and findings.

GOALS

The following goals, developed by all partners at our first convening, guided our research process:

I. ECOSYSTEM Define the field(s) and inventory the current ecosystem.

II. DEMOGRAPHICS Expand understanding of who participates in the field(s).

III. PRACTITIONER EXPERIENCES Establish a baseline understanding of practitioner experiences, how individuals came to this work (career path), barriers and opportunities practitioners (and their communities) face, and the support practitioners may need now.

IV. VISIONS & VALUES Capture practitioner visions of what is needed to transform and build the field(s) in ways that are inclusive and aligned with their values (social justice, social good, public interest, etc., as articulated by practitioners themselves), as well as how to mitigate threats.

V. STORIES OF SUCCESS AND FAILURE Document and distinguish models and approaches to carrying out technology for social justice (& etc.) work and projects on the ground. Identify what works, what doesn’t, and why.

Read more about the Funding & Advisory Organizations, Research Team (Coordinating Partners and Research Partner Organziations).

ECOSYSTEM

I think there’s a lot of small grassroots and community-based organizations that are doing really, really great work and hustling really, really hard, and because they’re so small and because they work specifically with People of Color, they definitely do not get the recognition that they deserve, and they don’t have access to opportunities like other bigger NGOs. — HIBIKI, DIGITAL SECURITY TRAINER

Our first research goal is to explore the current ecosystem by defining and taking inventory of the field(s).

Like a natural ecosystem, the ecosystem of people, organizations, and networks who work at the intersection of technology and social justice, social good, and/or the public interest is complex and constantly changing. We found:

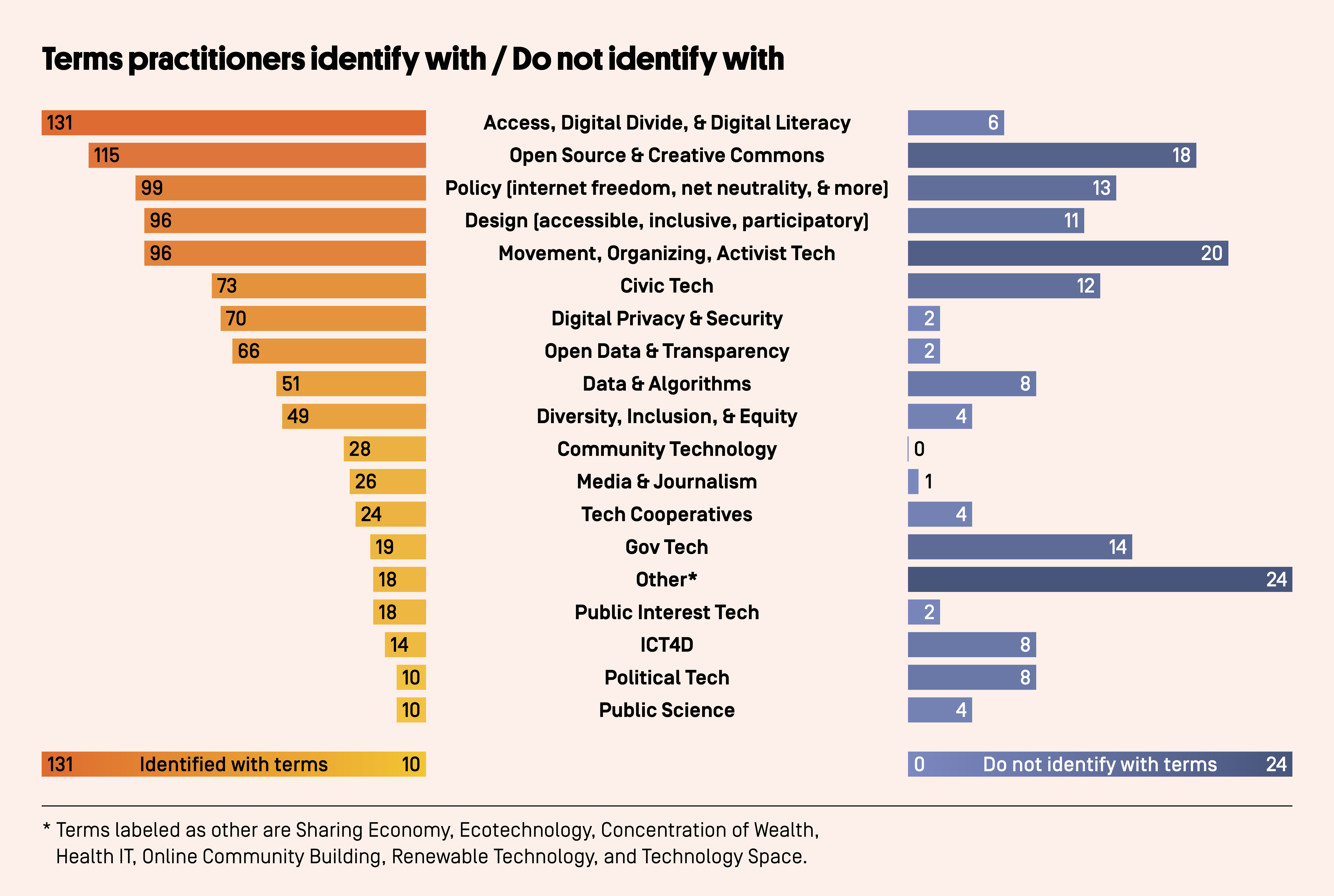

- People use many different terms and frames to talk about this ecosystem. Study participants identified over 252 terms to describe the work they do (see http://bit.ly/t4sj-terms-shared). We gave 96 participants a terms worksheet and asked them to select or add terms they identified with. The most frequently used terms included “free software” (selected by 40) and “open data” (37); “privacy” (36) or “security” tech (31); “digital literacy” (35); “open web” or “open internet” (30 each); “community technology,” “civic tech,” and “net neutrality” (28 each); “tech policy” and “inclusive design” (27 each). The terms that people found most problematic were “sharing economy” (18) and “smart cities” (14). We also coded all 215 terms into the following top-level categories:

- Many practitioners feel that differences between terminology and framing are important and should not be erased. Participants articulated clear differences between “civic tech,” “community technology,” and “public interest technology.” Many identify with one, but not another, of these terms. For example, some see “civic tech” as a field of practice that is predominantly white, male, U.S.-centric, and institutionalist. Several participants, mostly women, LGBTQ folks, and/or PoC who feel excluded or marginalized from other technology related spaces, said that they feel included in “community technology” spaces.

- Just one in five (18 out of 96) participants identified with the terms “public interest technology” or “public interest technologist.” Many think of these terms as primarily relevant to government technology, telecommunications policy, and public interest law.

- About half of study participants do not identify as “technologists,” even if they work extensively with technology, and in some cases, even if they are software developers. A few shared their experiences of men policing the meaning of the term. When asked to identify their role(s) in the field, half (52%) of participants selected “technologist” and 40% selected “community organizer.”

- Funders control the frame. Some practitioners described feeling pressure to frame their work in a certain way in order to have access to funding streams. A few explicitly rejected the introduction of new umbrella framings, such as “public interest technology.” Instead, they prefer to use terms and frames that are specific to the type of work they do, the values and politics they hold, and the communities they work with.

- Funding is unequally distributed among the various subfields in this ecosystem, in ways that replicate structural inequality. For example,study participants shared that in their experience, national organizations, organizations led by white men, and those with certain frames receive the lion’s share of resources.

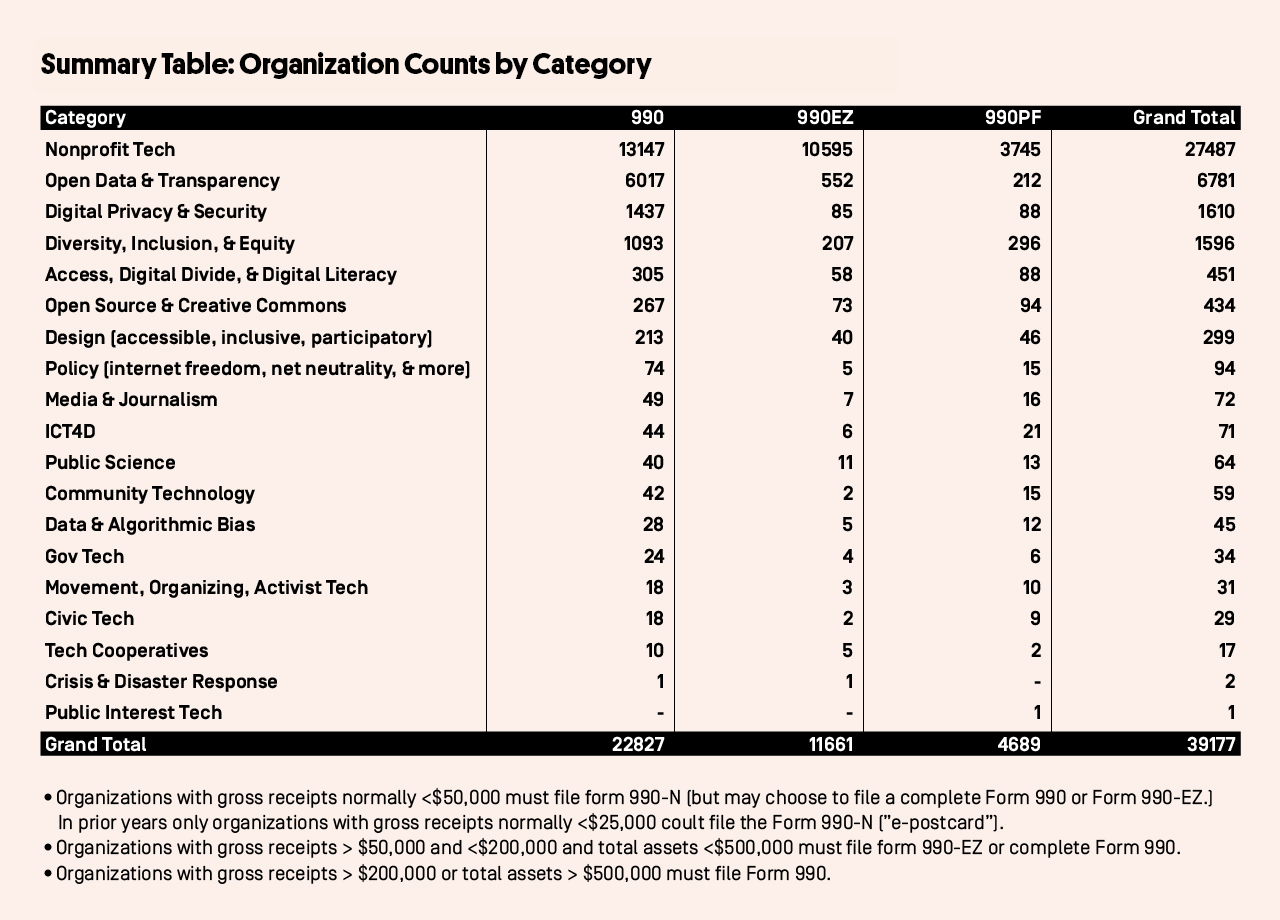

- There are thousands of organizations working in this ecosystem. We gathered a database of over 700 organizations and projects, identified over 40,000 nonprofit organizations from IRS form 990 data, and populated a spreadsheet with hundreds of educational programs and networks (both formal and informal) focused on helping people develop skills for this work. In addition to nonprofit organizations, participants said that tech cooperatives and collectives, membership organizations, and independent consultants provide key support for the technology needs of grassroots, movement-building organizations.

- A great deal of work is done by volunteers, nonprofessionals, and informal networks. This indicates the strength, breadth, importance, and attraction of the field. However, some participants feel that reliance on volunteerism has negative implications for inclusivity and sustainability.

- Practitioners across this ecosystem are doing transformational work, even in conditions of scarce resources. This is a diverse, vibrant ecosystem, and we found many powerful stories of success (see the Models that Work section of the full report for examples).

DEMOGRAPHICS

There’s this expectation of who you must be, and what your background should be like. I don’t have that background. That traditional background. It’s interesting, I’d enter a room and they’d act like basically I’m the one getting coffee. Being a person of color is still an issue in our sector, and it’s something we need to change. Also, not being male is an issue. Who’s getting the funding? Let’s take a look at that. — CHARLEY, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR AT A TECHNOLOGY NONPROFIT

Our second research goal is to expand understanding of practitioner demographics.

Racism, sexism, classism, ableism, transphobia, and other forms of oppression permeate the broader tech sector. Unfortunately, based on the experiences of study participants, the non-profit, community, and public tech subsectors we looked at are not immune to these problems. A total of 188 individuals participated in our research, including 79 focus group participants and 109 interviewees. A total of 121 individuals (64% of participants) completed the demographic questionnaire. We found:

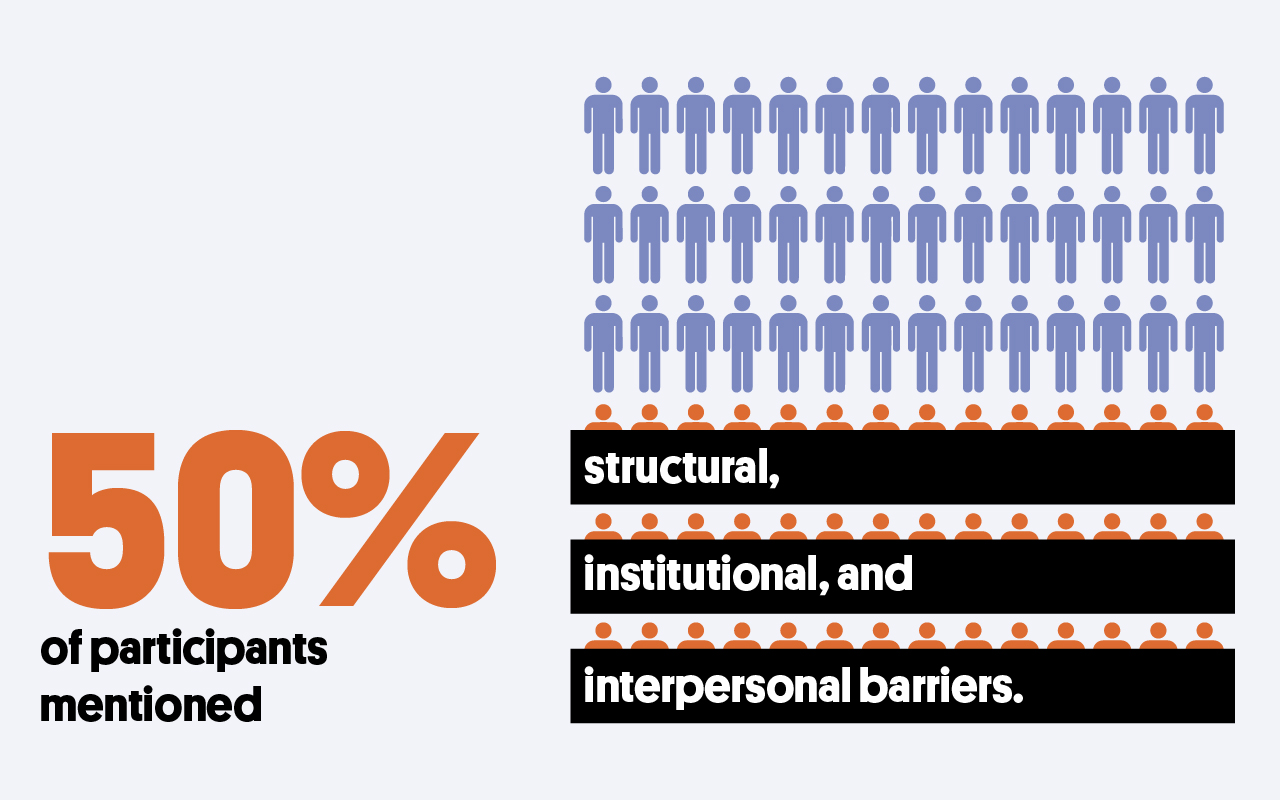

- Many practitioners (about 50%) shared experiences of intersecting racism, sexism, classism, ableism, transphobia, and other forms of structural, institutional, and interpersonal oppression while working in this ecosystem. Like the broader technology sector, in study participants’ experiences, this ecosystem is disproportionately dominated by elite white cisgender men in leadership and decision-making positions.

- This ecosystem lacks public demographic data about race, class, gender identity, sexual orientation, disability, and other important variables. Key actors in the space, including the biggest players such as Code for America and the Knight Foundation, have not historically tracked or publicly shared demographic data about their employees, volunteers, leadership, or grantees, although this is beginning to change. This undermines accountability for equity goals.

- There are a number of well-developed strategies for addressing diversity, inclusion, and equity. Practitioners shared existing strategies and suggested their broader adoption. Suggestions for best practices include: gather and share demographic data about field participants; publicly set equity goals with timelines; and adopt best practices in recruitment, hiring, and mentorship.

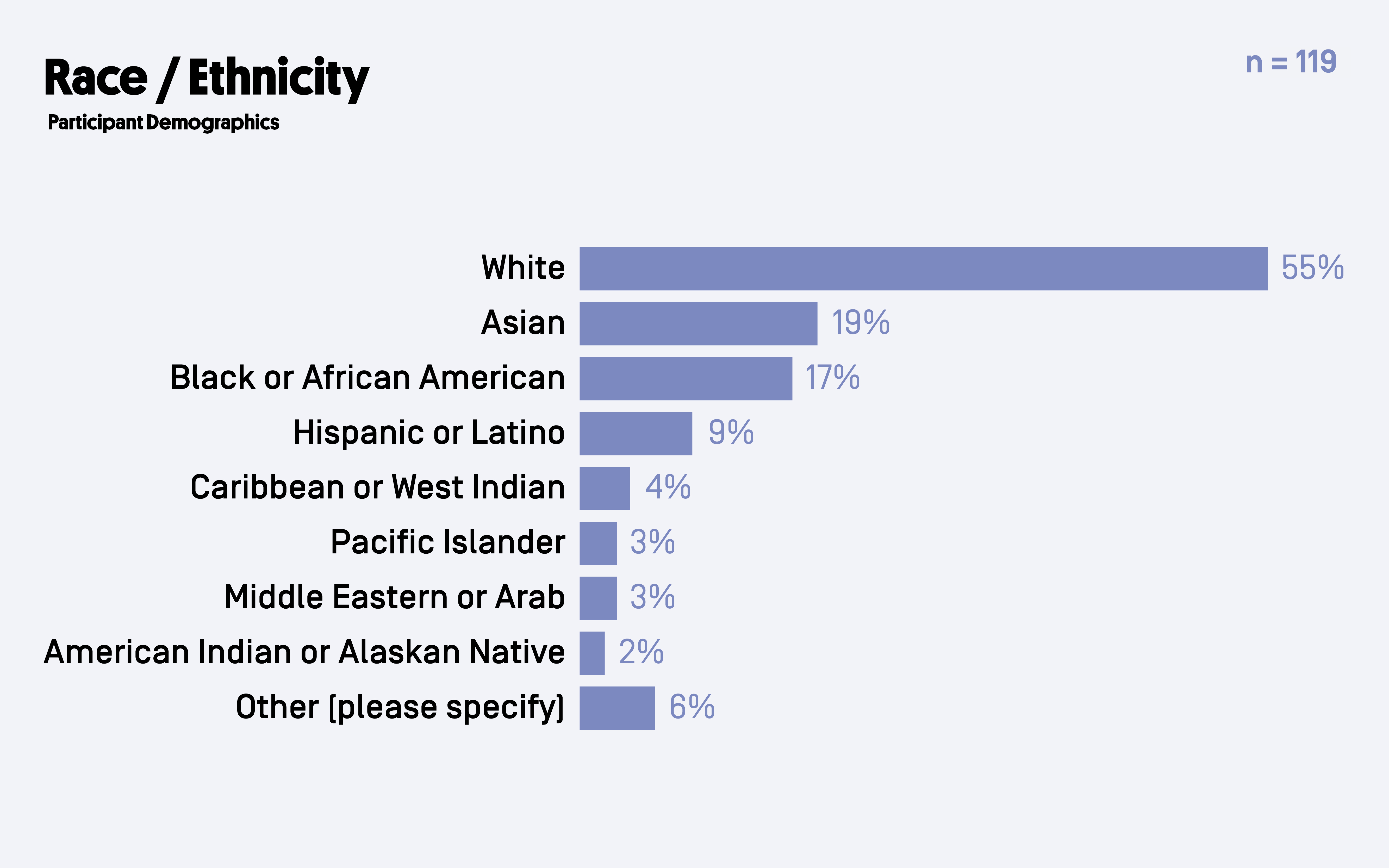

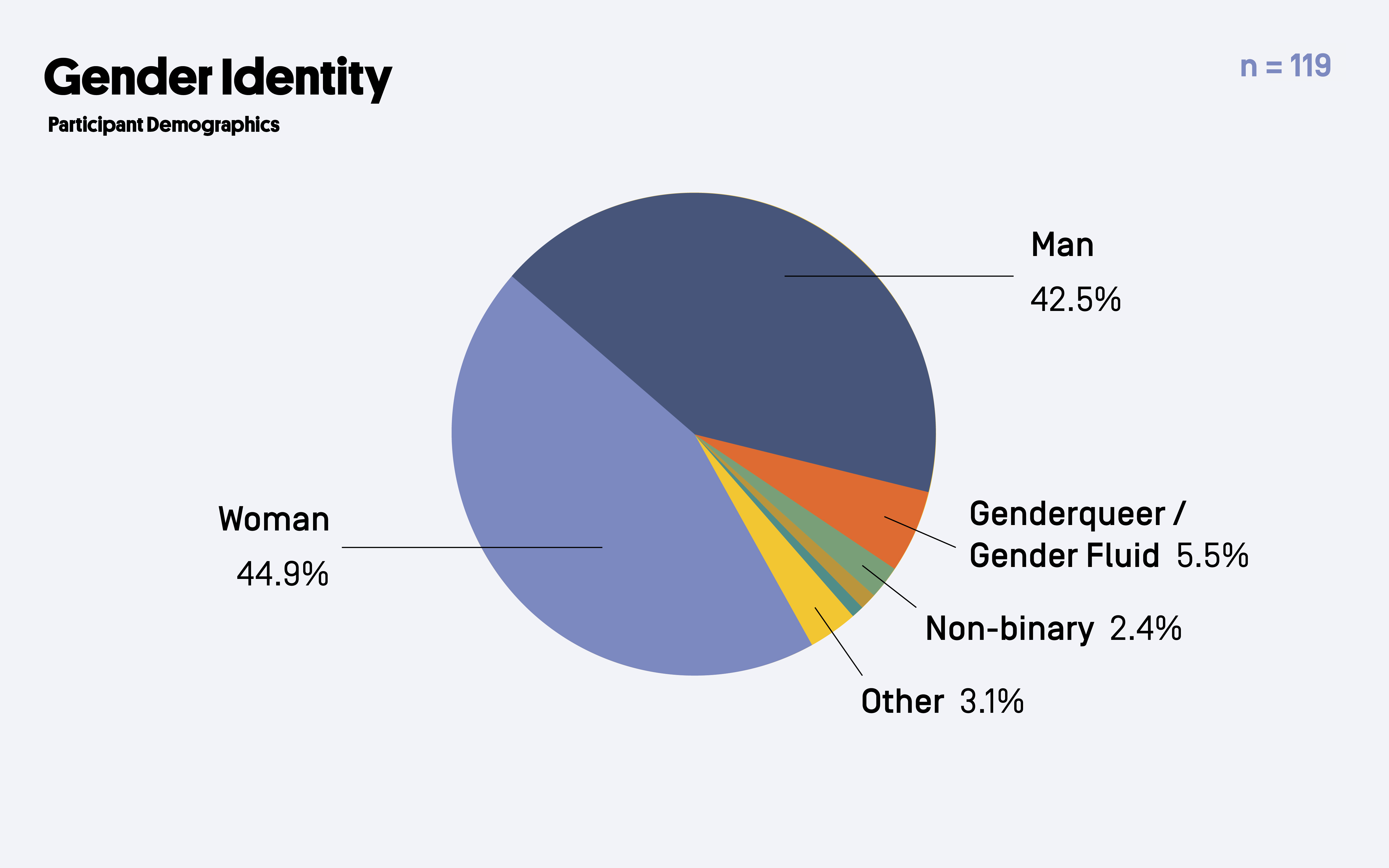

- Based on study participants’ experiences, this ecosystem is more diverse than the broader tech sector, but it still needs to be more diverse and inclusive. The ecosystem lacks demographic data, so we cannot make strong statistical claims. However, we trust participants’ statements about their lived experiences. We worked hard to include groups of people who are often marginalized in the broader tech sector in this study: of 121 participants who completed our demographic questionnaire, 55% identified as white and 45% as PoC. 48% identified as women, 45% as men, and 14% as genderqueer/ genderfluid, non-binary, trans, or other. 52% work for nonprofits, 25% in a for-profit business or cooperative, 14% in government, 9% in a foundation, and 8% in a university. Participants could choose more than one option, allowing the totals to be greater than 100%. More details are available in the Demographics of Study Participants section of the full report.

PRACTITIONER EXPERIENCES

I didn’t study technology in school. I didn’t go to school for tech. I did English and women’s studies. I’ve had very little formal tech education. Almost all of my learning has been on the job […] Well, tinkering as a kid and starting to play on the internet when I was younger. I could figure out some things online, and I could set up computers well for people, and parlayed that into working for nonprofit organizations in New York. — MATIJA, WORKER/OWNER AT A TECH COOPERATIVE

Our third research goal is to develop and share knowledge of practitioner experiences by establishing a baseline understanding of how individuals came to this work (career path), barriers and opportunities practitioners (and their communities) face, and the support practitioners may need now.

Practitioner experiences are quite diverse: there is no single pathway into this work. Many techies are self-taught, and there are many important roles besides software developer. Supportive individuals and mentors, networking, fellowships, conferences, and the movements they are part of are all defining factors in participants’ career trajectories into this work. Women practitioners said they must learn to navigate being a woman in tech, and they mostly have to work in and engage with hostile and blatantly sexist environments. Some participants also described their experiences of racism, classism, homophobia, transphobia, and other forms of discrimination. We found:

- There is no standard pathway into careers in this ecosystem, and there are many self-taught techies who play important roles across government, nonprofit, and movement tech work. A few practitioners described a mismatch between job requirements for Computer Science degrees and the skills that are really needed. To read more about practitioner pathways, see the Pathways/ Education/Career section of the full report.

- Many different roles are necessary for the successful integration of technology in social change work. Successful technology use in government, nonprofits, community-based organizations, and social justice movements does not exclusively, or even primarily, depend on software developers. Designers, project leads, community managers, researchers, communicators, and co-design facilitators are examples of other key tech roles that are important to success. Most crucially, practitioners emphasized that tech projects ought to include and/or be led by people with lived experiences that the projects aim to address.

- Supportive individuals (62%); conferences (40%); and fellowships, internships, and mentors (18%) are all key onramps to this work. The most frequent form of support mentioned by interviewees was supportive individuals (62%), followed by conferences (40%). However, participants also said that conferences are expensive, and that most have a long way to go in order to become inclusive, accessible, and affordable spaces that are welcoming to all.

- A small but growing number of formal educational programs are available to train people for careers focused on building, using, or engaging with technology for social justice and/or the public interest. For example, we gathered this spreadsheet of educational resources: http://bit.ly/t4sj-ed-programs. Participants noted that informal and community-based education is also important. Additionally, 10% of participants mentioned that tech bootcamps, hacker/ makerspaces, and tech meetups are potentially valuable spaces. However, most educational spaces and programs, whether formal or informal, do not yet teach an ethics- or values-driven approach to tech, and tend to replicate the sexist, racist, solutionist culture of the mainstream technology sector.

- 50% of participants mentioned structural, institutional, and interpersonal barriers in this ecosystem. Participants described racism (33%), sexism (33%), transphobia (10%), ageism against older practitioners in the tech industry and against younger people in civil service (9%), classism (9%), and homophobia (8%). Discrimination based on race, class, gender identity, sexual orientation, disability, and their intersections lead to practitioners feeling unsafe, and make it difficult for some to continue working within this ecosystem. Other barriers include difficulty finding community (29%), a lack of tech integration with core organizational work (22%), difficulty accessing educational programs (14%), and high participation costs.

- Many women experience sexism in this work, just as in the broader tech sector. Ten percent of study participants mentioned transphobia as a barrier. A few described racism, classism, and/or other forms of discrimination.

VISIONS & VALUES

Respect for the work that’s been done by other people. Because people are in this environment, the intersection of technology and social justice, they sometimes think that they still have more expertise than community organizations that have been doing this for a very long time. So I think that there’s a respect for the knowledge that’s already there, and accountability for the actions that we take. —JAYLEN, TECH CONSULTANT FOR NONPROFITS

Our fourth research goal is to capture practitioner visions of what is needed to transform and build the field(s) in ways that are inclusive and aligned with their values (social justice, social good, public interest, etc., as articulated by practitioners), as well as how to mitigate threats.

We asked practitioners about the values and principles that are most vital to their work, about what they see as the biggest threats to their values, and about changes needed to realize their vision and values. We also asked about threats to the field, community, and practitioners that need to be addressed or are currently being tackled. We found:

- Many practitioners are guided by values and principles of justice and equity. They seek to establish equitable and inclusive relationships, spaces, and technologies, as well as broader social transformation.

- It is fundamental to center community expertise and needs in tech development and implementation. The capacity to empathize with and understand others’ experiences and needs leads to more meaningful relationships and better uses of technology. Community leadership and accountability are key.

- Solutionism (belief in “silver bullets”) is a real problem, as is the “savior” attitude or approach many technologists take when working with communities. Technology sometimes harms users and communities, rather than helping them flourish. Many practitioners described examples of how tech work that is supposedly “for good” replicates the same inequities they hope to dismantle.

- It is hard, but necessary, to “walk the talk” in our own spaces. Truly innovative spaces are collaborative, inclusive, and diverse, and creating such spaces takes a lot of work. Power inequality within organizations, as well as competition for scarce resources, are problems for many practitioners.

- Free/Libre and Open Source Software is seen by many practitioners as crucial to growing and sustaining the ecosystem, because its values are consistent with their goals of equity and social justice, and because in practice it enables resource sharing around technology development, rather than competition.

- Practitioners identified the following six key threats to the communities they work with: state violence and surveillance; politically-motivated targeted digital attacks; marginalization based on race, class, gender identity, and sexual orientation; unequal access to digital technology; unaccountable corporate infrastructure; and limited resources. Additionally, practitioners pointed out that these threats, for the most part, are not new: they are long-standing systemic issues, amplified by new tools and platforms. For example,in the case of surveillance, practitioners noted that well-meaning white technologists have secured most of the available resources with narratives about “new” threats, even though Black, Indigenous, Muslim, Latinx, and Queer/ Trans communities have always faced state surveillance in the United States.

STORIES OF SUCCESS & FAILURE

The struggle is not ‘access to encryption tools.’ It is organizing day labor communities in order to protect against ICE raids, and things like that. We’re confusing means and ends. […] I think that’s the central problem that the technologists continually go through, is they pretend like technology is the thing that matters, when it’s actually people’s fight that matters and the outcome that matters. — GERTRUDA, DIGITAL SECURITY RESEARCHER

Our fifth research goal is to document stories of success and failure; distinguish models and approaches of carrying out technology for social justice work on the ground; and identify what works, what doesn’t, and why. We found: There are a number of models that work well, according to practitioners.

- Community-led design is the most successful model, according to participants from all sectors (government, for-profit, nonprofit, and social movement). It is crucial to involve people in the design of technology that is supposed to benefit them, and to do so at all stages of the design process (not just at a moment in the beginning).

- Cross-sector partnerships and relationships help catalyze project success.

- Public campaigns can pressure large institutions to make positive changes.

- Certain crisis response tasks can be crowdsourced using new digital coordination tools.

- Information and communication technology (ICT) infrastructure projects, such as fiber rollout or municipal or community wireless, can be excellent opportunities to create citywide coalitions, connect diverse actors, and build community power.

- Technology can be used to expand access to legal services. Organizational clarity about politics and ethics is an important way to attract mission-aligned work.

- Resilient solutions work better than “cool new tech.” Many practitioners said that although it is important to maintain, upgrade, and support proven tech solutions, most resources and attention go to new tools.

We also asked participants to describe models that don’t work. They said:

- Models that lack community accountability usually fail. Engagement with communities on the ground is essential. “Silver bullet” approaches not only tend to fail, but can harm communities. It is important to center community needs over tools. (For examples, see the Stories of Success and Failure section of the full report).

- “Parachuting” rarely works, although it is often well funded.

- Funders often support projects that sound exciting or “innovative,” presumably based on personal relationships or a “cool” new technology, but these fail if they do not emerge from a real community need.

Finally, we asked for concrete stories of success, and we asked practitioners about how they evaluate their work. There was no single evaluation rubric; instead, success is contextual and based on organizational goals. Participants gave a very wide range of concrete success examples. These included stories about how people and organizations were able to:

- Pass surveillance oversight ordinances;

- Create a trans-inclusive workplace;

- Convince city departments to open their data;

- Make data meaningful for individuals in the community;

- Crowdsource aerial damage assessment to reduce wait times for FEMA aid;

- Demonstrate eviction impacts to state policymakers;

- Use disaster recovery funds to catalyze new technologies and innovative small businesses;

- Link federal ICT infrastructure grants to community organizing;

- Create a PoC and women-led makerspace;

- Convince multinational firms to fix security vulnerabilities through public exposure;

- Build one-on-one relationships with tech company legal teams, which led to a pro-privacy brief from a multinational telco;

- Build a community-controlled mesh network; and

- Achieve widespread adoption of end-to-end encrypted messaging.

These are only a few among many stories of success that practitioners shared with us. We hope that this report contributes to many more such stories in the future, and we urge widespread adoption of our recommendations.

CONCLUSIONS & RECOMMENDATIONS

We gathered hundreds of recommendations from a wide range of practitioners. We synthesized these into five key recommendations that we feel apply to all actors across the ecosystem. Targeted recommendations for specific audiences (Tech Practitioner Orgs, Other Orgs, Individual Practitioners, Funders, Educators, and Government) are available in tables at the end of each main recommendation in the Recommendations section of the full report.

1. Nothing About Us Without Us: Adopt Co-Design Methods and Concrete Community Accountability Mechanisms.

Tech project design must involve people from the communities the project is meant to serve, early on and throughout the design process. We recommend that practitioners from all sectors:

i. Adopt co-design methods. Most crucially, tech projects should be grounded in real-world community needs, and be led by or include organizations with deep domain knowledge. These methods have a growing practitioner base, but could be better documented.

ii. Develop and adhere to specific, concrete mechanisms for community accountability. For example, funders and municipalities might prefer or require tech projects to present a concrete community accountability plan across all stages of design, testing, and implementation.

iii. Invest in education (both formal and informal) that teaches co-design methods to more practitioners. Support existing efforts in this space, create new ones, and push existing educational programs and institutions to adopt co-design perspective and practices.

iv. Create tech clinics modeled on legal clinics. Public interest law and legal services work are client-oriented, and lawyers doing this work are constantly interacting with and learning from people who need to navigate larger systems. Tech can learn from this model.

v. Do real usability testing, and create community research and design groups. Usability testing is essential to validate assumptions and create usable UX and UI. For broader oversight, set up Community Design Boards for technology design projects, similar to Community Review Boards for research projects.

vi. Create fellowships to spread co-design methods across multiple fields, not only in tech, but in other areas as well, such as legal services.

vii. Avoid “parachuting” technologists into communities. Instead, prioritize resourcing people from the community to build their tech skills. This doesn’t mean “no outsiders can help a community,” but projects with outside support work best when they help develop community capacity to take over, maintain, and grow the project in the long run.

viii. Stop reinventing the wheel. Allocate increased resources for capacity building, maintenance, and improved usability of existing proven tech, not just pilots of new tools.

2. From Silver Bullets to Useful Tools: Change the Narrative, Lead with Values, and Recognize Multiple Frames and Terms Across the Ecosystem.

We found that there is no singular field that contains everyone who is working with technology for social justice, the public interest, and/or the common good. Instead, there is a complex ecosystem. Terminology and framing matter, as does the narrative about what this work is about. Language choices are political and typically will attract some people but alienate others. Recommendations in this area include:

i. Be clear about values and vision. Regardless of how you or your organization think about the role of technology in social change, it is important to be explicit about your values and vision. For example, for many practitioners we interviewed, social justice is the core value, and technologies are tools to support movements that advance towards social justice. For others, such as many of those working in the public sector, accessibility and efficiency are core values, and tech is a tool to make government services easier to use.

ii. Shine a light on the amazing diversity of people who already work in this ecosystem. It is important to lift up diverse practitioners in the public conversation about this work.

iii. Challenge the narrative that tech work lies only in the corporate sector. Emphasize that folks can make a life out of tech work that will support them, their communities, and their values.

iv. Challenge the narrative that the “most exciting” tech work is only in for-profit startups. Produce and circulate a new narrative about the very wide range of roles, problems, challenges, and opportunities to do tech work in public, nonprofit, and movement organizations.

v. When circulating jobs, grant opportunities, procurement bids, and other resource opportunities, consider that any frame you choose will make some communities feel more comfortable than others. For example, many women and PoC feel pushed out of “technologist” frames, even if they have tech skills.

vi. Acknowledge that technology often reproduces longstanding problems. For example, surveillance is not a “new” threat for Black people in America. Listen to, support, resource, and center practitioners from communities that have been dealing with issues for a long time, even if there is a new technological manifestation of the problem.

3. #RealDiversityNumbers: Adopt proven strategies for diversity and inclusion.

Racism, sexism, classism, ableism, transphobia, and other forms of intersectional oppression permeate the broader tech sector, and the ecosystem we looked at is not immune. All actors should adopt evidence-based best practices to advance diversity and inclusion, such as:

i. Gather and share demographic data about grantees, employees, volunteers, leadership, and boards.

ii. Create and publicly disclose timebound diversity targets, and create specific plans and deadlines to diversify leadership.

iii. Adopt tried and true techniques for inclusive workplaces, such as codes of conduct, community agreements, diverse project teams, and anti-oppression trainings.

iv. Invest in inclusive hiring, mentorship, retention, and advancement, implement wage transparency, and create paid fellowships and internships for people who are Queer, Trans*, Women, Black, Indigenous, and/ or People of Color.

v. Transform conferences, convenings, meetups, and other gatherings to be far more diverse, inclusive, accessible, and affordable. Adopt best practices for inclusive events, such as the DiscoTech model. Do the same at key sites such as libraries, universities, community colleges, hacklabs, and makerspaces.

4. Developers, Developers, Developers? Recognize Different Roles and Expertise in Tech Work, and Support Alternative Pathways to Participation

Tech work is not performed only,or even primarily, by software developers. Across the ecosystem, all actors need to acknowledge the different roles that are necessary to effectively use technology for social justice, the common good, and/or the public interest, in order to build a more inclusive ecosystem that offers opportunities to those who might otherwise be excluded by a narrow definition. Additionally, since many people in the space are “self-taught techies,” organizers turned sysadmins, political campaigners turned web designers, and so on, we must create supports for people who enter tech via alternative paths, such as mentorship programs and fellowship cohorts. We recommend:

i. When hiring tech teams, create positions for roles such as graphic designer, product manager, community manager, co-design facilitator, researcher, communicator, or popular educator, in addition to developer, regardless of sector (government, nonprofit, for-profit, cooperative).

ii. Establish support for mentorship. Supportive individual relationships (mentorships, in workplace and educational spaces) were mentioned by practitioners more frequently than any other support mechanism as critical to their career path. Create a mentorship matching program, especially to connect mentors that share aspects of lived experience with mentees. Increase support, recognition, awards, dedicated community networks, and other mechanisms to improve mentorship across the ecosystem.

iii. Create paid fellowships and internships that support people from existing organizations, and from marginalized communities, rather than just the one-year parachute model. Create paid opportunities for students of color in other fields, such as law, public administration, and public health, to learn about how tech design processes work.

iv. Create a program for diverse practitioners to visit schools and universities and talk about their career path and work.

v. Demonstrate pathways into tech for social justice, the common good, and/or the public interest. Make these careers visible in mass media, social media, and popular culture.

vi. Focus on digital equity and popular education to expand the pipeline of people who see themselves as part of the ecosystem. There is a crucial role for people who are able to work as educators in frontline communities that are most affected by the application of digital technologies.

5. Coops, Collectives, and Networks, Oh My! Support Alternative Models Beyond Startups, Government Offices, and Incorporated Nonprofits.

Interesting tech work is done by groups that do not fall into the standard models of for-profit startups, government offices or agencies, or nonprofits. Tech cooperatives and collectives provide key tech services and infrastructure to thousands of movement groups and nonprofits. Informal networks can rapidly coalesce during moments of crisis and provide improved information flow, identify priority needs, and organize large numbers of volunteers around tech work with very little resources. Membership organizations also provide tech infrastructure in ways that are accountable to the needs of social movements. All of these are crucial but less visible forms of organizing tech work for social justice; they should be recognized and better supported.

i. Explore how to help non-501(c)3 organizations, such as B Corporations, worker cooperatives, member organizations, and ad-hoc networks support themselves and provide living-wage jobs for their employees while also doing tech work for social justice.

ii. Provide startup and conversion funds for tech coops, both to help with new tech coop creation and to support coop conversion of existing companies.

iii. Provide tech coop development support including incorporation templates, legal incorporation support, operating agreements, and other resources that will help more tech company founders consider coops. These should be standard within tech incubator programs, in university offices that are dedicated to helping create startup spin-off companies, and in municipal initiatives (such as economic development offices) to support new business creation.

iv. Provide rapid turnaround support for ad-hoc networks. Often, especially in crisis moments, ad-hoc and informal networks mobilize very quickly to provide tech support. In many cases, they are more effective than traditional organizations. Develop mechanisms to support such networks.

v. Leverage ICT Infrastructure projects to grow the ecosystem. These projects can draw together city governments, community-based organizations, policy folks, and technologists. Successful models from Detroit (DCTP), Philadelphia (MMP), and New York City (Red Hook, Rise : NYC, public housing broadband, etc.) should be supported and widely replicated.

vi. Use government procurement to grow the ecosystem. This requires focused initiatives that can help smaller organizations and companies, women and PoC-owned firms, coops, and others navigate the procurement process.

SUMMARY OF RESEARCH OUTPUTS

In addition to this written report, our research team produced the following outputs:

- Data Gallery: Three Data Galleries, or printable slide decks of key quotes, findings, and data visualizations, for use at face-to-face workshops and project convenings, as well as for online circulation. The final data gallery is here: https://morethancode.cc/assets/resources/More-ThanCode-Data-Gallery.pdf.

- Practitioner Profiles: 13 practitioner profiles, in a journalistic style that describes each person’s work, their career path, and challenges and opportunities they faced along the way: http://morethancode.cc/.

- Key Interview Takeaways: Key takeaways from all interviews: https://morethancode.cc/assets/resources/T4SJ-Key-Interview-Takeaways.pdf.

- Data Visualizations: A gallery of interactive data visualizations, IRS form 990 data, job data, and more: https://public.tableau.com/profile/t4sj#!/.

- Powerful Quotes: An interactive tool of powerful, paragraph-long quotes from interviewees, categorized by our top-level research goals: https://morethancode.cc/quotes/.

- Organizational Database: Information about 732 organizations and projects, available both as a spreadsheet (http://bit.ly/t4sj-orglist) and via a searchable web interface: https://morethancode.cc/orglist/.

- Nonprofit Database: Data about 39,000 nonprofit organizations relevant to this ecosystem, according to their tax forms (IRS form 990): https://public.tableau.com/profile/t4sj#!/vizhome/T4SJIRS990/SummaryTableCountsofOrganizationsbyTypeperCategory.

- Educational Programs Spreadsheet: A publicly editable spreadsheet of educational programs, fellowships, bootcamps, meetups, and other relevant educational resources: http://bit.ly/t4sj-ed-programs.

- Jobs Database: A database of relevant jobs to help us understand how employers think about this work: http://jobs.morethancode.cc.

- Terms List: A spreadsheet of all terms mentioned by practitioners to describe the work they do. Includes tabs for the full list, a count of participant identification with terms, top-level categorization codes, and counts of organizations that use terms in IRS form 990: http://bit.ly/t4sj-terms-shared.

- Research Instruments: Throughout the project, we made all research instruments publicly available, including our final semi-structured interview guide: https://t4sj.co/ uploads/resources/T4SJ-interview-guide-II.pdf and focus group guide: https://morethancode.cc/assets/resources/T4SJ-Focus-Group-Guide.pdf.